Echos of the Age of Exploration and Discovery

Natural history museums are boring- bottled specimen; stuffed animals, long dead; aging habitat displays; and don't forget those herbarium exhibits- brown and definitely prone to crumbling should they be handled with anything less than extravagant care. The subtle whiff of the lab bench blending with the feeling of dust. How long should a leaf be kept, 10 years, 50 years, 200 years...

For most of my life I have loved museums, art museums. The paintings representing a spectrum of genres and styles, spanning the range of human emotion, telling stories using a fantastic array of complimentary figures and subtexts. An art museum is a place where there is no draw upon your time, nothing you ought to be doing, a place where, for the length of the trip through the exhibition, you are called upon only to enjoy, only to live in the moment. To communicate with the painter on a visual, visceral,emotional, or spiritual level. It is a place of intense beauty, an empty hall with windows into a thousand distant worlds. Worlds perched in as many different eras and corners of the earth. And in addition to all of that it is fantastically beautiful.

A natural history museum is not. It is none of those things. It is the encyclopedia, neatly displayed in the center of a library bursting with fascinating stories. It's neat tomes forming a catalogue of knowledge seldom consulted except for by a select few who like that sort of thing. A few people to whom random facts can be amusing.

For much of my life this was my opinion.

I would occasionally go through a natural history exhibition if it happened to be in a place I was already at, but my interest was at best superficial. If the displays were well done, they became the center of my attention; 'Oh', I would say to myself, 'What a wonderful method to house these thousand ancient apples. The black room, the mirrors, and little light boxes are so clever they almost make one forget that they encase yet more geriatric apples'.

My science courses at university, far from helping to bolster my interest actually created the opposite effect. I was all too able to muster up the smell of formaldehyde or feel the dust of deteriorating leaf when standing before an exhibit.

You may be surprised to read this, since, if you have been reading the blog for any length of time, or follow me on any of my social media accounts, you will be aware that I am a natural history artist. I go to the natural history museum for fun, I collect found objects on holiday and even on walks, and I have sketchbooks full of botanical sketches. So, what changed? Are the museums better than ever before? Are the displays more interactive- the specimen more exotic?

To a certain degree they are. Modern methods of display are certainly less fusty, and I enjoy the modern presentation. They are not however the reason for my developed love of these catalogues of the exotic.

History is a succession of stories. Stories of the joys and sorrows of the human experience. Epic tales of the passions of the human soul. It captures examples of the achievement of things that are secretly hoped for in the bosom of every man or woman. Bravery, betrayal, adventure, glory, power, fame, great sacrifice, and every other peak to which we aspire or shirk. And perhaps no time in history, or at least recent history has been so overflowing in its generous examples as the renaissance and the age of enlightenment. Following the middle ages, the rise of humanism spurred on a race for knowledge and with that knowledge, ability. To know and to know how to do are some of the cornerstones of the modern university system. They are the principles behind the scientific method. The underpinnings of modern medicine and the foundations of the reinvention of philosophy- (I am speaking here only of the modern era, the ancient Greeks, the Romans, Egyptians, Mayan, and Chinese are all older than the period of which I write).

They bought to western civilization a thirst for knowledge whose reverberations can still be felt today. A fascination not only with the natural world but with the human mind and it's thirst for understanding. No subject was to large or small, to far away or theoretical to analyse. From the movement of the planets to the workings of the insides of the body, areas of confusion were teased apart like knotted hair at the mercy of a fine tooth comb, sifting, weighing and isolating facts.

We owe so much of what we know today to these movements. We also bear the burden of the babelesque mentality that sometimes accompanies them. And of course we have the 'evidence' of the explorations. the materials left to us by our forefathers; instruments, calculations, books, sketches, and exotic natural objects.

Maria Sybille Marion traveled through the amazon, illustrating butterflies and exotic plants, Lewis and Clark traveled across north America documenting native plants as they looked for a way to the pacific Ocean. Ferdinand Bauer joined 5 other scientists on a trip to Australia where he used a compicated colour coding system to produce a catalogue of highly accurate illustrations. Alexander Von Humbolt traveled the world as a geographer and naturalist becoming one of the first people to describe human induced climate change. All of these explorers collected of brought biological specimens back with them.

Today we have maps, satellites, encyclopedias, the internet. What is left for us to explore? We know what space looks like, and if Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are correct we will soon be able to go there on holiday. We have documentaries and photos of the deepest oceanic trenches. We have hand held microscopes and even ultrasound machines that attach to mobile phones. Yet this information seldom inspires awe in us. We take it for granted.

About three years ago I took my first online scientific illustration course. Joining several hundred other students worldwide I began drawing my way through nature over a course of six weeks. Being based in Australia, and having therefore an overly weighty Australian contingent of students, I began to be intrigued by the results of each assignment pouring in. The simple task of drawing three object yielded so many exciting and unusual things, some of which I could not even identify. when we came to plants, the diversity and magnificence was unexpected, and when at last animals were the subject I struggled to compete.

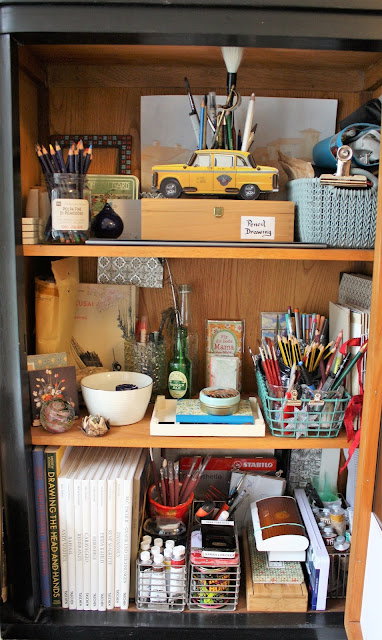

I began to understand the pull. I began to feel the magic that goes with seeing things for the first time in an unexpected context. The fascination of nature in its most exotic forms. In essence I began to understand the mentality that led to so many huge natural history collections. And I began to build my own.

William T. Cooper describes how exotic birds were prepared and shipped on long journeys to Europe where the wings were carefully spread out to be painted by naturalist illustrators. Never having been seen alive these illustrators often created magnificently detailed illustrations of the creatures posed in ways that are not seen in nature. The works themselves are of interest both for their skillful execution and for their insight into the experience of new discovery.

Humbolt is often said to have invented or discovered nature in the way we now understand it. Not as a force to be battled and feared as it was in the middle ages but as a thing of intricate beauty to be enjoyed and explored. This modern view is central in western culture today. Nature has become our playground and a place to relax and re-balance ourselves.

|

| A 'unicorn horn' in the treasury museum in Vienna |

When I walk into a natural history museum I am brought face to face with the age of discovery; with the daring explorers who traveled to the ends of the earth bringing back the things that amused and surprised them. Within it's halls, often unfortunately displayed, lay the passions and enthusiasms of a former generation. Often amassed over lengthy periods of time. Items so rare that they were passed on from generation to generation, or so valuable that they were left to the museum or state for care.

We do not always think of seashells, seed pods, and bones in this light. But we are not, despite our advanced surveillance of the world that far from those days. And perhaps we ought to take a break, from time to time, to think about the elegance and diversity of this highly intricate world in which we live.

If you liked this post you might also enjoy:

- Finding Joy in preserved Nature

- Inktober- Nature's Treasures

- Botanical Illustration vs. Botanical Art

To get posts as soon as they are published click on the subscribe button at the top of the page or Follow by clicking on the follow button.

And if you haven't watched my skillshare class have a look at at it:

skillshare class information or go straight to skillshare

Comments

Post a Comment