The difference between Botanical Illustration and botanical art

For some reason, botanical art has made a big come back in the last few years. But with a fresh kick. The delicate pastel roses of the late eighties, early nineties have been replaced by the vibrant colors of exotic plants or the deep greens of jungle-like houseplants. When Ikea picks up a style it seems it has really made it. With botanical illustration, motives come other scientific illustrations, old charts, vintage school poster reproductions, and animal and plant art. It recently came to my attention that the term botanical illustration, botanicals, and botanical art, have been being used more or less interchangeably. You may ask why anyone should care. And although it is always nice to use the proper names of things and be specific about what is being discussed, the reason for making a distinction is more weighty than grammatical accuracy. So without further ado here are a few of the differences:

Purpose:

While any of the above names describe illustrations that would be nice to look at botanical, and other scientific illustrations are created for their use in science whereas botanical art is created for its aesthetic appeal. A botanical or scientific illustration functions as a visual identification key. |

| botanical illustration |

|

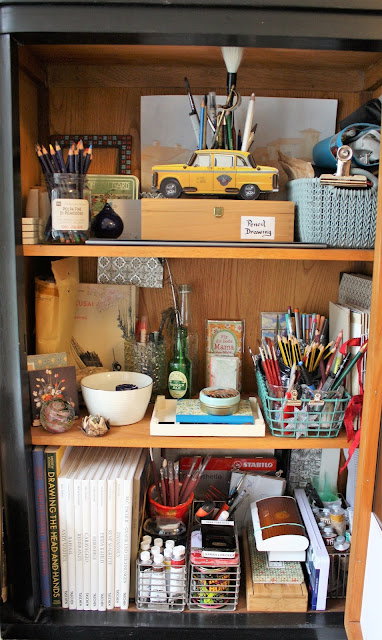

| botanical art on the easel |

Layout:

The goal of the layout of botanical art, or wildlife art, or marine art,... is beauty, drama, action or appeal. Colors, form, angles, and position are all tweakable in the pursuit of these criterion. Here we see nature both inspiring and being inspired by art.A scientific illustration is beautiful by default. I am sharing here a beautiful illustration created yesterday by artist Sharon (Sion) Thomas in the context of a natural history illustration course we are both participating in at the moment.

Click on the highlighted link above if you want to see more of her work.

I chose her illustration partially because it is really well done, and partially because the layout is clear and neat. On this illustration, the flower is drawn not only from a variety of perspectives but also in it's dissected forms. As a result, the unique details specific to this plant are easily identifiable. It is also notable that the parts of the plant being illustrated don't need to be complete, as long as the symmetry is indicated, a partial drawing yields all of the necessary information. Notice how the drawing in the left bottom corner is split down the middle and shows both the top and bottom forms in a single sketch. This is sufficient for its purpose of identification. The various parts of the plant are also labeled according to function. At the top, the flower is shown in its natural presentation so that a person unfamiliar with the plant would know how it is found growing in nature. Color is also indicated, although the plate itself s not colored. The one missing component on this page would be measurements. To make it truly useful each component would be labeled with its size in millimeters to give the viewer a concrete idea of how big it is. This may seem obvious to us now. Practically everyone has seen or had fuschias in the garden, but it is important to remember that the golden age of illustration was also the golden age on exploration and many of the things that people were observing and drawing or recording were new to the eyes of those receiving the illustrations. Therefore notes and detailed observation, as seen above, are extremely valuable in interpreting the illustration.

A finished plate need not have sketches, measurements, and notes to be a scientific illustration, but it would be the end product of those notes and the measuring, observing and color swatches.

proportions:

In a scientific illustration, the proportions within the drawing are carefully and accurately representative of the natural object. Often they are a median derived from study of multiple or even hundreds of specimen. They represent the average height, color, and shape of the species being represented. This is not always the case in botanical art. Although the subject is usually clearly recognizable, the artist has the freedom to play with the proportions to suit his or her style and goal. This is why the head of a flower is sometimes bigger than the stem, the flower is simply given a straight stem, or the leaves are less or more significant than the flower itself. These changes can create drama in the picture but they immediately move it into the category of art and out of that of scientific illustration.Specific information:

Because the goal is identification and description a scientific illustration contains as many specific details as possible. Colors are carefully evaluated and reproduced to be used in determining whether the object is the 'real thing' or not. Many plants look a lot like their poisonous twins. A scientific (in this case botanical) illustration will give the information needed to make the critical distinction. One of the interesting examples of this I ran across while drawing food sources of swallowtail butterflies two summers ago is the wild carrots similarity to hemlock. Knowing the difference can be a matter of life and death. The wild carrot can keep you alive in the wilderness and is one of the easiest wild plants to find and eat. Hemlock, on the other hand, is one of the famous poisons used in the middle ages. Just drop it into the goblet of your enemy and down he goes. I wouldn't like to be the illustrator whose work was vague and led to a mix up between these two plants.Below are two pictures I found on Pixabay showing Hemlock (top) and wild carrot, also known as Queen Anne's Lace (below) beside one another. They are quite similar and would be easily confused for one another if the illustrator didn't observe and record their characteristics carefully. In a case like this, it is not important to know the characteristics of both, or how they differ from one another. It is important that the one which is being documented is clearly and exhaustively recorded. When this happens the observer cannot fail to realize that he is looking at something else if he has the wrong species.

|

| Hemlock, rounded flower balls |

|

| wild carrot, cup-like flowers |

Thus all botanical illustrations are botanical art, but not all botanical art is botanical illustration. This is applied to animal art or illustration and any other type of natural history illustration as juxtaposed with nature (wildlife,etc..) art. As for botanicals, the term seems to be an umbrella term sometimes used to refer to all of the above but more often used when the speaker means, 'plant related' but is, as yet. unsure of the correct term.

So what is the use of scientific illustration in this modern era of cameras, videos, and smartphones? Well, for one thing, illustrations don't have fuzzy spots or areas. The detail is uniformly precise as you move from the front to the back of the subject. This creates a much more specific picture than is usually available with a lens. (I do realize that there are a lot of wonderful tools that photographers use for adjusting the color in their images, and while I think they do an amazing job, I still feel that the 'real' colors on a page better mimic nature). Natural objects also have texture, fur, feathers, spines, scales, and bark, just to name a few. These textures can be varied on even the smallest surface areas. The human eye is more adept at picking out these intricacies than a camera is, and hours of time allow the illustrators to record each of the textures they see.

So now to you, do you illustrate, or do you like illustrations? If so which do you prefer? The slightly chaotic, yet structured scientific illustrations or the polished, artistic botanical/wildlife/... art?

Let me know in the comments.

I post three times a week; Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday. To get posts as soon as they are published click on the subscribe button at the top of the page or Follow by clicking on the follow button.

Comments

Post a Comment